I would like to discuss an attack on the U.S. Capitol in this column—not the one that occurred on January 6, 2021, but the shooting of U.S. congressmen by Puerto Rican nationalists in the House of Representatives chamber in 1954. Though smaller in scale than the 2021 attack, the incident was still shocking, especially the fact that active members of Congress were struck by live bullets.

Before getting into the attack itself, I’ll briefly summarize the history between Puerto Rico and the United States that led to the shooting. Puerto Rico had been a Spanish colony for about 400 years since 1508, but in 1898, amid the movement for independence of South American countries, an autonomous Puerto Rican government was finally established. This independence, however, did not last long. During the Spanish-American War, American troops occupied the island, and afterwards, in 1900, Spain “gave” Puerto Rico to the United States. Puerto Rico then became a part of the United States under a status in which residents receive American citizenship but are not allowed to elect members of the federal government. Later, in 1948, a law was passed that strictly forbade any moves leading to Puerto Rican independence. In response to this repressive U.S. approach, pro-independence groups staged protests in various parts of Puerto Rico, but all were violently suppressed. In November that year, two Puerto Rican nationalists attempted to assassinate then-President Truman. The resulting fierce firefight saw one police officer on guard duty and one of the attackers hit by bullets.

It was in the midst of this momentum for independence that four Puerto Rican nationalists carried out their 1954 attack on Congress. Their leader was 34-year-old Lolita Lebrón, who had been drawn toward pro-independence ideology since she saw Puerto Rican nationalists massacred during a peaceful street protest as a teenager. Her feelings were further strengthened by witnessing the anti-Puerto Rican discrimination and the poverty of Puerto Ricans in New York City, where she had moved to make a living. She became a member of the pro-independence Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and carried out the 1954 attack after years of correspondence with the party’s leader, Pedro Albizu Campos, who had previously encouraged armed uprisings on the island.

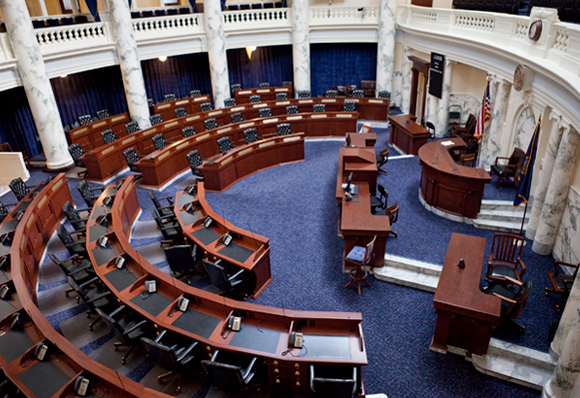

On the day of the attack, her fellow three conspirators hesitated to go through with their plan, but Lebrón declared that she would go on alone and continued toward the Capitol. Moved to action by this determination, the remaining three followed her inside. The security officers they encountered asked if they had cameras (which were not allowed inside), but did not find their guns. The group reached the visitor’s gallery above the House of Representatives chamber, where Lebrón shouted, “¡Viva Puerto Rico libre!” (“Long live a free Puerto Rico!”) The group then fired a total of 30 bullets onto the floor below with semi-automatic pistols, hitting five congressmen, one of whom suffered a serious chest wound. Of the four perpetrators, three were captured immediately, while the fourth fled the scene and was later taken into custody. At their trial, they were sentenced to over 50 years in prison. 25 years later, President Carter commuted the sentences of three of them (the fourth had been released shortly before that due to terminal cancer). The reason, according to one theory, was in exchange for American prisoners of war in Cuba. Regardless, the perpetrators were freed and returned to their native island of Puerto Rico, where they received a hero’s welcome from their supporters. Lebrón lived out the rest of her life there, marrying and eventually passing away in 2010 at the age of 90.