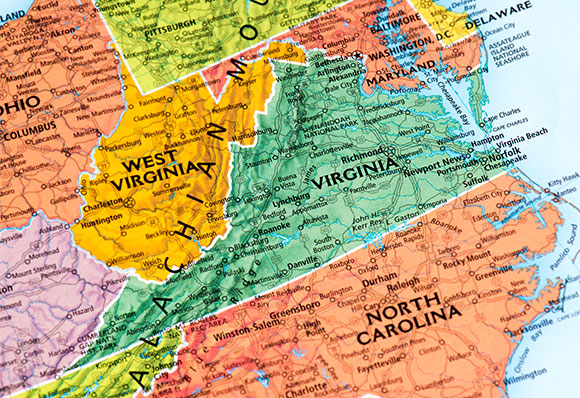

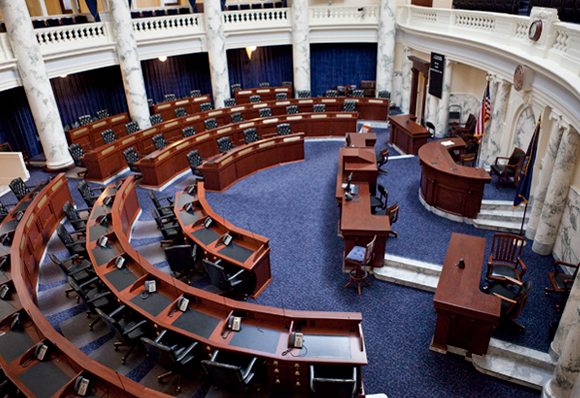

In this article, I want to talk about a shooting that took place at a courthouse in Virginia – a state that straddles the line between North and South. In this incident, the defendant in a case, and his family, who were unhappy with the decision rendered by the judge, opened fire, killing 5 people.

This is not a story about some circuit court in the Wild West (the western frontier of the U.S. during the mid-late 1800s often characterized by outlaws and violence), much as it may seem to be. This story takes place in 1912, when the U.S. was producing 300,000 Model T Fords per year and Japan was just ringing in the end of the Meiji Era. This is a story about an incident that took place during that period, in a courthouse in Carroll Country, Virginia, just on the Virginia side of the North Carolina border.

It all starts with a young man kissing a young woman at an event in his hometown. But this young woman was also involved with a different man, and as one would expect, the situation became something of a mess. The ensuing quarrel was not settled that day, but continued into the next morning, when everyone in the town was gathered at church for services. Both men roped their friends and families into what would become a massive fight. The young man and his brother drew their weapons at mass, and both were charged with disturbing the peace. The brothers fled to North Carolina where they were soon after arrested.

The brothers were handed over to the deputy sheriff and his posse, who were then stopped in their tracks by a man on horseback: Floyd Allen, the principal figure of our narrative. Allen was the uncle of the wo brothers, the head of the Allen family, and quite well known locally as the owner of a large plot of land on which he ran a business. Allen became incensed when he saw two members of his family tied up in the back of the deputy sheriff’s carriage, and when the deputy sheriff demanded that Allen let them pass, Allen drew his gun, struck the lawman with it, and released his nephews. Although Allen later forced his nephews to turn themselves in at the courthouse, the state prosecutor indicted Allen and several other members of the Allen family on charges of obstruction and assault.