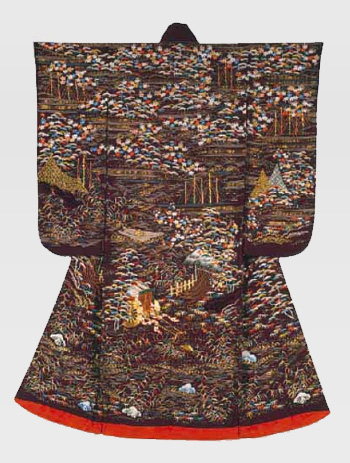

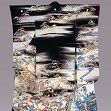

This is a kosode believed to have been produced in the latter half of the 1670s. By around 1650, the Tokugawa government's power had been consolidated. As the national policies inclined toward civil administration, the standard of living improved. In 1666 (sixth year of the Kambun era), a fashion book (Shinsen On-hiinagata) illustrating new kosode patterns was published for the general public. The publication of this type of book indicates that social changes were taking place. The kosode patterns illustrated in the book suggest that T-shaped kosode were treated as a canvas, with patterns arranged on their right half. We do not know why this layout was preferred, but as this kosode pattern arrangement is so unique, we now call it Kambun pattern or Kambun kosode.

This work is an excellent example of a Kambun kosode. The curved wooden bridge is expressed with the kanoko shibori (literally “fawn spot tie-dyeing”) technique, and the cherry blossoms are embroidered. The characters for “flower” and “spring” are embroidered with gold thread. The design places a strong emphasis on the cherry blossom; our national symbol as well as a symbol of spring. The creation of such new designs is proof that the kosode became a popular fashion item.